Interview: Magda Biernat

Magda Biernat received the Film Photo Award in the spring of 2021. One year later, DM Whitman and Magda have a chat about her project.

© Magda Biernat

DM Whitman: Hi Magda, I am so interested in your work. I first became aware of it at FotoFest 2022 in Houston. Can you provide a little bit of background about yourself?

Magda Biernat: Sure thing. Yes, it’s funny that we both noticed each other’s work at the FotoFest Portfolio Night and now have been matched together to discuss this project. It’s a small world.

So, I am originally from Poland, and I moved to the United States in 2002 after I graduated from my university. Besides Marketing and Management, I also studied photography in Poland and as most photographers, at the beginning I was into black and white street photography. Enamored with the work of Magnum photographers, I applied for an internship at the agency after moving to NYC and I ended up working there for almost 4 years. It was there, on West 25th Street, that I learned the ins and outs of the photography business and made friends for the rest of my life. But while at Magnum I also realized that documentary photography and photojournalism wasn’t quite for me and after some constructive feedback from some of the Magnum photographers I turned my camera towards architecture and interiors. I took a workshop in Maine and started working with my teacher Norman McGrath as his assistant and soon after I got my first architectural assignments. I’ve been doing that for 16 years now and I love it. My personal work is also influenced by structure and form, and I tend to focus my lens on the built world. I think my personal and commercial work feed each other. But in order to focus on my personal work I occasionally need to leave NYC for a while. I’ve always had a longing for “somewhere else", it’s an escape, adventure, “something new” that I crave and that inspires me. Most of my projects are created during travel. My husband Ian and I have done two one-year-long trips so far – one around the world, which my “Inhabited” and “Betel Nut Beauties” series came from. And the second South to North, from Antarctica to Alaska through all the Americas and that trip resulted in my recent series and two photo books “Adrift” and “The Edge of Knowing,”

© Magda Biernat

© Magda Biernat

© Magda Biernat

two photo books “Adrift” and “The Edge of Knowing,”

DW: Who and/or what are your influences and inspirations?

MB: My first influences were Magnum photographers such as Henri Cartier Bresson, Bruce Davidson—and later, Trent Park, Mark Power and Alec Soth. But as soon as I got more into an architectural type of photography I was inspired mostly by the photographic archaeologies and typologies of Bernd and Hilla Becher and the photographers from their Dusseldorf school - Candida Höfer and Thomas Struth. Currently though I am inspired by the works of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg and her extensive travels over the last 40 years. I hope to accomplish as much as she did in her life. It’s an incredible archive.

DW: Your oeuvre of work contains threads on cultural identity and borders. How did this interest develop for you?

MB: That’s a good question. As a person who moved from my home country and created a home away from home in a different country, I have always had this feeling of belonging neither here nor there - in a state of “in-betweeness”. I am not displaced, I chose to move and leave my home country behind, but I still don’t feel like I entirely belong. I will always embody the hybridity.

As for my interest in borders, I grew up in Poland before the fall of the Berlin Wall, where we didn’t have a lot of freedom of movement. As a family we travelled quite a bit, but we were not allowed to go West, which made us want to cross the border even more, yearning for the “greener grass on the other side”.

Since then I’ve been fascinated with the transient nature of what we tend to see as permanent borders. Few borders have ever truly stopped the mixing of people or cultures. The theme of rivers and seas has also long been present in my work. In my MFA graduation project - a three-channel video installation entitled 6,654 kilometers/4,135 miles I delved into the seawater connection between the Atlantic and the Baltic Sea by physically mixing the waters, bringing one to the other and I questioned the transformative quality of locations and geographies at a time when individuals are no longer bound to one particular place.

Also, “The Edge of Knowing” book and project I mentioned earlier deals with the themes of borders and borderlands, by trying to redefine what “America” is and by creating sort of a “Pan-American” vision. The images in the book are in no chronological or geographical order, so the viewer can create their own version of the Americas – jumping back and forth between North, Central and South, exploring the similarities and differences between them all without quite knowing what is where. A big part of “The Edge of Knowing” is the text, which Ian wrote, printed on pages of a re-imagined Pan-American passport. The US sometimes seems caught up in the differences between it and the other American countries, but maybe as a European, I couldn’t help but see how new, and similar, they all felt.

© Magda Biernat

© Magda Biernat

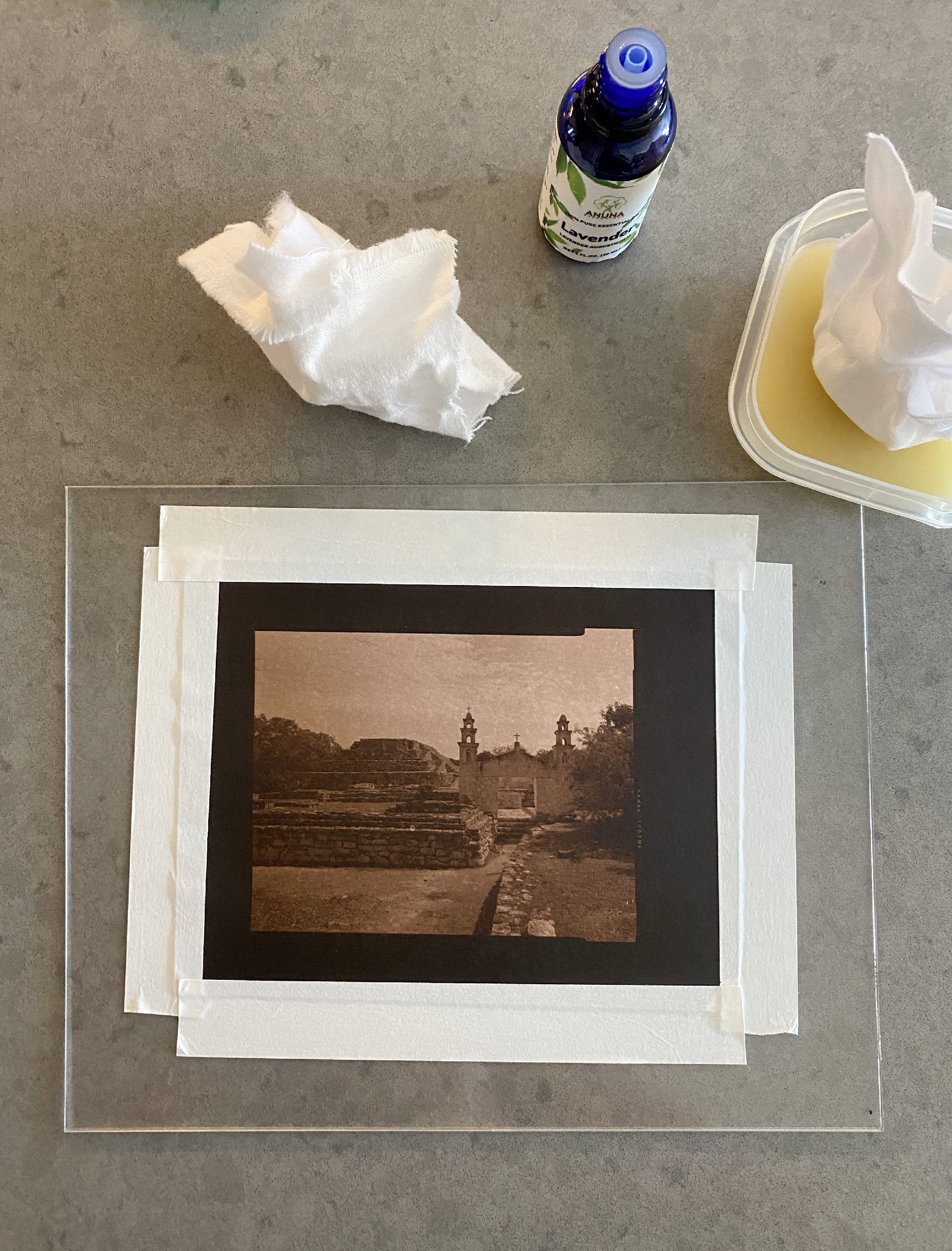

DW: The series Salt Front you nod to Talbot and this earliest of photographic printing processes. What drew you to working with salted paper?

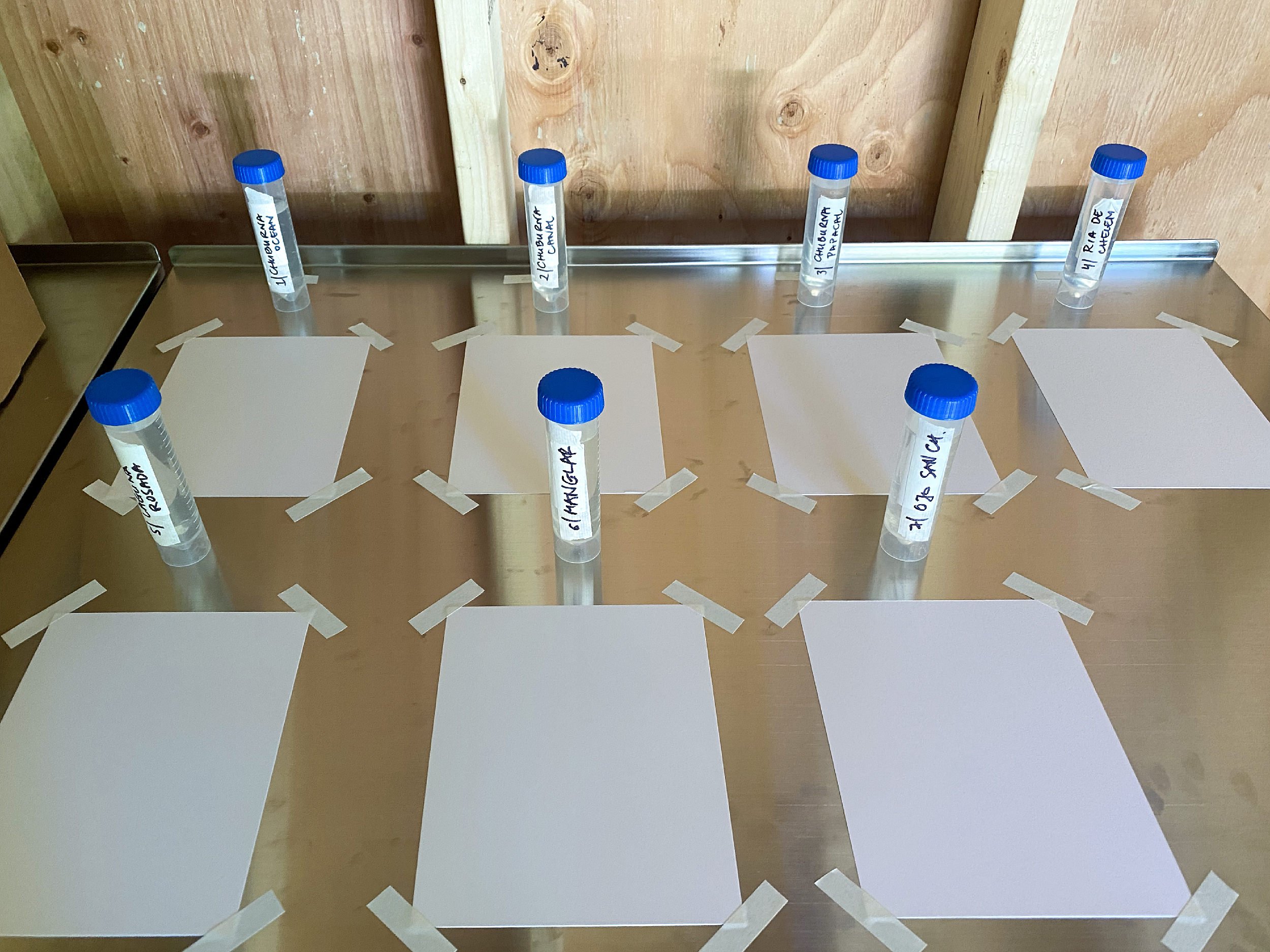

MB: The idea for the project came first. I was intrigued by the places where the river meets the sea, and where freshwater mixes with salt water. It occurred to me that this state of the brackish water would make for a great metaphor for the mix of cultures, and the salt front that moves with the tides and changes with season, as a great metaphor for shifting borders. Then I remembered I once read about the salted paper process and the thought came to mind, what if I was to collect salt water from different estuaries and use it as a base for my salt prints,wat effect would I achieve? And knowing that the “controlled” proper way of making salt prints is by using a 2% salt solution to a 12% silver nitrate solution, I started to wonder what would happen if I used different levels of salinity to make the prints.

DW: And did you investigate this prior to the inception of Salt Front?

MB: No. I’ve never worked with any alternative processes before, so this was all new to me. It is definitely challenging and I had made many many experiments and mistakes, but in the end I am not looking for a “perfect” print. It’s all about the imperfections and variations.

DW: … and the overall concept and intention it would seem.

MB: Yes, definitely.

DW: Can you provide context about the use of text and the analytical data provided for in the presentation of the images? How did you decide to include this? And why do you believe it is important?

© Magda Biernat

MB: Well, I thought that the images themselves needed some context. The project is kind of complex in nature. I felt like the viewer should know that all the 6 prints had been developed using different salt samples which might be unclear if I didn’t include the different salinity ratios underneath the prints. As I worked on the project it was also interesting to me to discover how soon the salt disappears in some of the estuaries and how far the saltwater goes in the others. So including the graphic representation of the salt collection points was to illustrate those differences. Then also I wanted to highlight the fact that the project alludes to border themes and I decided to add the ethnic mix information to the panel. In addition, the subject I chose to photograph and print using those 6 different salinity samples, needed some context, as those were all interesting places I found.

DW: How did you determine the subject or location for each of the pieces?

MB: I spent several days driving around each estuary collecting water samples in different points and looking for subjects for my photographs. In each location I was looking for something that would follow a theme of cultural cross-pollination that the brackish mix represents. I searched for places either historically or culturally significant but also for things that were out of place, that felt a bit like they didn’t belong. Two words came to mind: encroachment and incongruity. I like finding things that are out of balance, misplaced, unnatural to the environment. But I guess I was also looking for integration - trying to find layers of cultures that are interconnected. Basically, something to connect with the themes of shifting borders and hybrid cultures.

© Magda Biernat

© Magda Biernat

© Magda Biernat

DW: Why film? What is it that is important to you in the work? Is it process, materials, or something else?

MB: Why film? Because I love how it slows me down. I work with digital cameras all the time on my architectural assignments, but for my personal work, I like the limitations of film. The number of frames on a 120 roll of film, or number of sheets of film and film holders I have with me. It makes me more selective about what I photograph and how.

DW: I also wonder if it supports or provokes something that we can’t necessarily find words for- it satisfies something in us....

MB: Yes, yes, yes! I totally agree.

DW: The images as presented invoke a sense of “citizen science” with the depictions of salinity ratios alongside the images which we can compare. Did you, or do you consider that an aspect of the work, or is purely sociological or something else?

MB: I don’t claim to be a scientist, just a citizen. But yes, this is a pretty unscientific overview of some pretty complex issues about immigration and assimilation, and about salinity in estuaries. At the very beginning I consulted a friend who is a professor of Coastal Oceanography in Mérida, Mexico. He helped me to understand measuring salinity and some of the science behind fresh and saltwater convergence. I realized it would be really easy to get overwhelmed by the technical side of things and decided to use my samples as more a metaphor for cultural mixing. However, I wanted to get a somewhat accurate reading on where the salt front was on the day that I visited those places. Getting a highly scientific reading would require much more time and equipment.

I like presenting an overview of both the salinity numbers and immigration and assimilation statistics as a jumping off point for thinking about salinity in estuaries as metaphor for cultural diversity.

© Magda Biernat

© Magda Biernat

DW: How has the award from Foto Film supported your work?

MB: The Foto Film Award made this project come to life. Before that it was just an idea I had, and I wasn’t sure what would come out of it. After I received the grant, I had to try and do it.

It also allowed me to come back to my 4x5” camera. For most of my personal projects I still use film but I travel mainly with my medium format camera, a Mamiya 6, as it is very portable and I feel very comfortable with it, it’s like an extension of my hand. But I have not used my large format camera in many years now, and it was nice to come back to it.

The award also pushed me to work on the project, with a yearlong deadline, I tried to photograph as many estuaries and deltas as possible within this year. I have not had a darkroom space before either, so this project made me create one.

DW: I completely understand that. Necessity can be the best impetus for “getting things done”.

MB: It certainly works for me. I am most productive when I have 100s of things happening at once and deadlines on the horizon.

© Magda Biernat